This set of three pieces began with the composition of the Violin Sonata. At the time of sketching it I found that there were several coincidences occurring, the most significant of which was that I had become curious about my own personal reactions to the death of my mother, and how extreme my response to the event had been. Secondly, I wanted to write some chamber music after having done a lot of work on my orchestral piece “Points of Decision”, and an opportunity arose for a performance by my two friends and colleagues at Atlantic College. Furthermore, I had found the mechanical part of a musical box that played a very simple C major tune, when clearing my mother’s house, and I became ever more curious about why my mother had kept it and what had been its history in our household. Thus, Part I of the triptych became the Violin Sonata, which became a vehicle for understanding the process by which an extreme emotional state can be ameliorated by time, as if the energy of a wound-up spring is gradually used up, leaving it in a relaxed mode. This became quite fascinating for me, and in different ways both Part I, and Part II for Concertante Oboe, Strings, Harp and Percussion, reflect the process of change, and of understanding extreme emotional states, the Violin Sonata doing it more succinctly, more abruptly, perhaps, in an intimate manner, while Part II uses a greater time scale, and a larger canvass.

I obviously realised that such a subject cannot be successfully dealt with in a single work, and so decided to write a triptych of pieces, all related to the same conceptual idea, and that they should gradually increase in size, occupying ever larger time scales, and at the same time be for increasingly larger forces, as if mirroring the process inherent in the conception but in a macro view. It felt right that a clearer reconciliation of one’s own emotive response to such a subject as this could only come through a deeper, broader investigation of it. It seemed necessary, too, with Parts I and II being instrumental music, that words should have their say in the matter, and so Part III contains settings of poetry that became relevant to the theme, for Soprano and Baritone soloists and large orchestra. However, on reflection I have lately decided to revise this score to include another poem and use a mixed chorus in some of the settings.

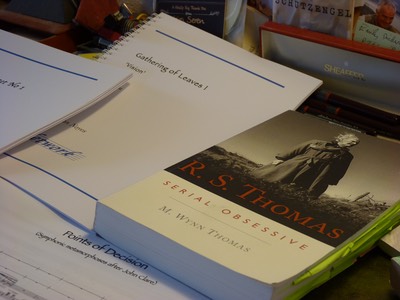

The title is a quotation from a poem by R.S.Thomas, and tersely creates a vivid picture of elderly persons just on the ‘margin’ of their own ‘eternity’ prior to the moment of their death. Typically of the poet, he prefers not to sentimentalise the situation but rather acknowledges this ‘moment’, one that we will all go through, and in that way goes some way to understanding it, if only because we have made ourselves aware of it by writing about it, by bringing it into the open, so to speak. This is why I have written these pieces, not to sentamentally linger on the death of my parents, but to acknowledge their passing, and in doing so to reflect upon their lives with gratitude. For me, it was a significant moment, although pondering such things seems to be unfashionable these days in the musical world, I think that any writing should be concerned with how an author reacts to the world around him. All art has done this.

There are more detailed descriptions of each of the three pieces given below, as programme notes.

Part I – Sonata for Violin and Piano

– the discovery –

Elements of the little C major tune of the musical box, are formed into the main theme of the sonata, heard at the very outset. This is very lyrical in itself, but in contrast, there are moods of great anxiety which disrupt the flow of lyricism, and it is this opposition of moods which propels the music, searching for more settled ‘normality’ in the form of the musical box tune which appears in the piano part towards the end. However, this idealistic stability is unseated by the reality of the moment, which is the fierce realisation of sudden death, and its contingent absoluteness, nothingness. Musically, the sonata concludes somewhat inconclusively, with the running down of the musical box and its attendant violin theme.

Although the issues here are ‘big’ in themselves I felt that using an intimate genre would encapsulate the directness and immediacy of the emotions that are felt in such situations. I had just brought in “the tea things” (John Betjamin – see Part III).

Part II“.. the Hour of Lead..”

Concertante Oboe, Strings, Harp, and Percussion

– the reaction –

After great pain, a formal feeling comes –

The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs –

The stiff Heart questions was it He, that bore,

And Yesterday, or Centuries before?

The Feet, mechanical, go round –

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought –

A Wooden way

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone –

This is the Hour of Lead –

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow –

First – Chill – then Stupor – then the letting go Emily Dickenson

Emily Dickenson’s poem vividly describes the extreme feelings that I experienced one morning many years ago when I discovered that my mother had passed away during the night. Reflecting upon this, both during the weeks and months immediately after this, and also a year or so later, made me question how it was that such intense emotions can be gradually accommodated, ameliorated, so that acceptance, and understanding, of the sadness occurs. This composition tries to explore the process of gradual change from an intense harsh emotion to one of calm gentleness through the amelioration of dissonance, angularity, and hemiola, to consonance and . This is simply put, but it takes place through a musical discourse which explores melodic and harmonic ideas initially used in Part I of the triptych “..the margin of eternity..”, and in the context of a concerto style where a solo Oboe plays an important role in projecting those intense emotions, though the rest of the orchestra is equally important. The E/F/E figure which opens the Violin Sonata figures prominently in this music, and the little C Major tune that appeared at the end of that piece (Part I) is importantly responsible for the reduction of dissonance through the latter stages of the composition. Thus, there is continuity between parts of the triptych, which reach its conclusion in Part III.

Part III “.. the world’s question..”

Song Cycle for Soprano, Baritone, Chorus, and Orchestra

– the understanding –

Given time, the extremes of emotion subside, and then questions begin to appear: the “why’s”, and perhaps even the metaphysical ones. Asking oneself about such questions was, for me, quite cathartic, and even the process of finding the right questions to ask, was, in itself, valuable. As is often the case, it is not necessarily the answers which are important, but rather finding the appropriate questions. Thus, the poems chosen have formed part of that process, and been instrumental in attaining a certain “acceptance” on my part, which I hope is mirrored in the music.